Threshold Review: FSLabs A321ceo for MSFS

February 13, 2025

Introduction

Launched in late 1988, the Airbus A321 was the first derivative of the A320, bringing a stretched fuselage whilst keeping the same wingspan, warranting extra payload capabilities while also retaining commonality in the flight deck, thus not requiring any extra training or certifications for A320 type rating holders.

Its maiden flight only went on to happen five years later, in 1993, with two prototypes rocking the two engine options at hand: IAE V2500 and CFM56-5B, with the IAE being the first one to roll out of the factory in early March, followed by the CFMs two months later.

Lufthansa (Germany) and Alitalia (Italy) were the first customers, ordering 20 and 40 aircraft respectively. By late March 1994, both already had their first units and were already commencing their commercial operations with the new plane.

The main differences to the A320 include its lengthened fuselage (6.94 meters longer), and slight wing differences, now featuring double-slotted flaps and minor trailing edge modifications, increasing the total wing area by four square meters. The reinforced wing area allows it to boast a 93,000 kg maximum take-off weight on the newer configurations (the first variant had a 83,000 kg MTOW).

The A321-100 did not end up selling well, with only 90 produced. Its limited range, combined with unimpressive MTOW and overall sluggishness relative to its sheer size made it an underwhelming product for most carriers. It did not help that the North-American market was still getting acquainted with the concept of fly-by-wire aircraft and only ever so shily embracing the then still pretty new A320.

In an attempt to conquer the competitive North-American market and offer a true alternative to the Boeing 757, Airbus went to the drawing board again to create the A321-200, a longer range version of the A321 with higher thrust engines, larger fuel tanks, and a substantially increased maximum take-off weight (as previously mentioned). With its advent, Airbus now had an offering capable of flying transcontinental legs in the United States with no issues whatsoever.

Unlike the first variant, the A321-200 was a huge success, with the deliveries progressively increasing since its release in 1995, totaling up to 1,784 built between its production lifespan.

The 2010s ultimately solidified its success after the airline market saw great increase in passenger demand for high density legs, with the deliveries jumping from double to triple digits and consistently sitting there nearly until the end of production. It was ultimately more successful than its main competitor (739ER), and its rival of yore was no longer in production (757), making it a relatively easy choice for most carriers around the globe.

Flight Sim Labs’ A321Ceo for Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 aims to bring an accurate rendition of the A321-200 and its four variants (wingtip fence and sharklets, with CFM56 or IAE V2500 engine option), allowing desktop pilots to experience the thrill of flying a “living” machine with service based failures, custom flight model, fully functional circuit breakers, an advanced autoflight system, a comprehensive electronic flight bag, and more.

The company rose to fame in 2016 with the release of their long-awaited A320-X add-on for Microsoft Flight Simulator X, ultimately being the first company to ever develop an in-depth rendition of the Airbus A320 for home simulators and ending a waiting period that went on for decades prior.

Their A320-X product went on to become one of the most popular add-ons for the ESP platform, collecting praises from multiple customers and flight simulation media for its realism, system acuity, and flight model.

Its eventual transition to Prepar3d in 2017 culminated in its solidification as the benchmark for flight simulation add-ons, going above and beyond what the other developers were creating at the time with the introduction of features such as full ACARS simulation, realistic icing, allowing virtual pilots to feel just a bit closer to what goes on behind the scenes of operating an airliner.

After a four-year long wait, Flight Sim Labs’ first product for Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 has rolled out of the production line, promising to bring even more depth and realism than every single one of their previous iterations. Could it be the next benchmark of overall fidelity in the simulator? We’ll find out.

First Impressions

I could not possibly hide my excitement when Flight Sim Labs officially announced the A321ceo for Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 in November 2024, but at the time I couldn’t help but wonder whether it would bring anything new to the table in an ever so saturated add-on market full to the brim of Airbus aircraft with varying levels of depth and quality.

While it was known they would be releasing the A321 first due to the existence of a very popular A320 add-on already (Fenix Simulations), the race to put the first A321 out for the simulator was lost earlier in the same year, making one even wonder on whether they’d even bother with continuing the development.

The existence of a competitor product with allegedly the same amount of simulation pedigree could have been a wall too high to climb for Flight Sim Labs, understandably so, as it’s ultimately hard to justify buying something you already have and happen to be satisfied with. Therefore, they had to face the challenge of going above and beyond to offer something that could potentially blow the competition out of the water in a field they have years of experience in: realism.

Excelling in that aspect could be the difference between “more of the same” or becoming the de facto Airbus A321 experience in Microsoft Flight Simulator, which would require careful evaluation from my attentive eyes to judge - albeit subjectively given my non-expertise as merely a Desktop pilot - whether they excelled or failed at said task.

The evaluation started with a Lufthansa flight, and it couldn’t have been any different given it was the first airline to ever take delivery of the A321 in early 1994. The airframe of choice (D-AISB), albeit not 1994 old, was also a certified cult classic, rolling out of the factory in 1999 and still serving Lufthansa after 25 years! A respectable service time, one could say. Oh, if only we had an EIS1 cockpit…

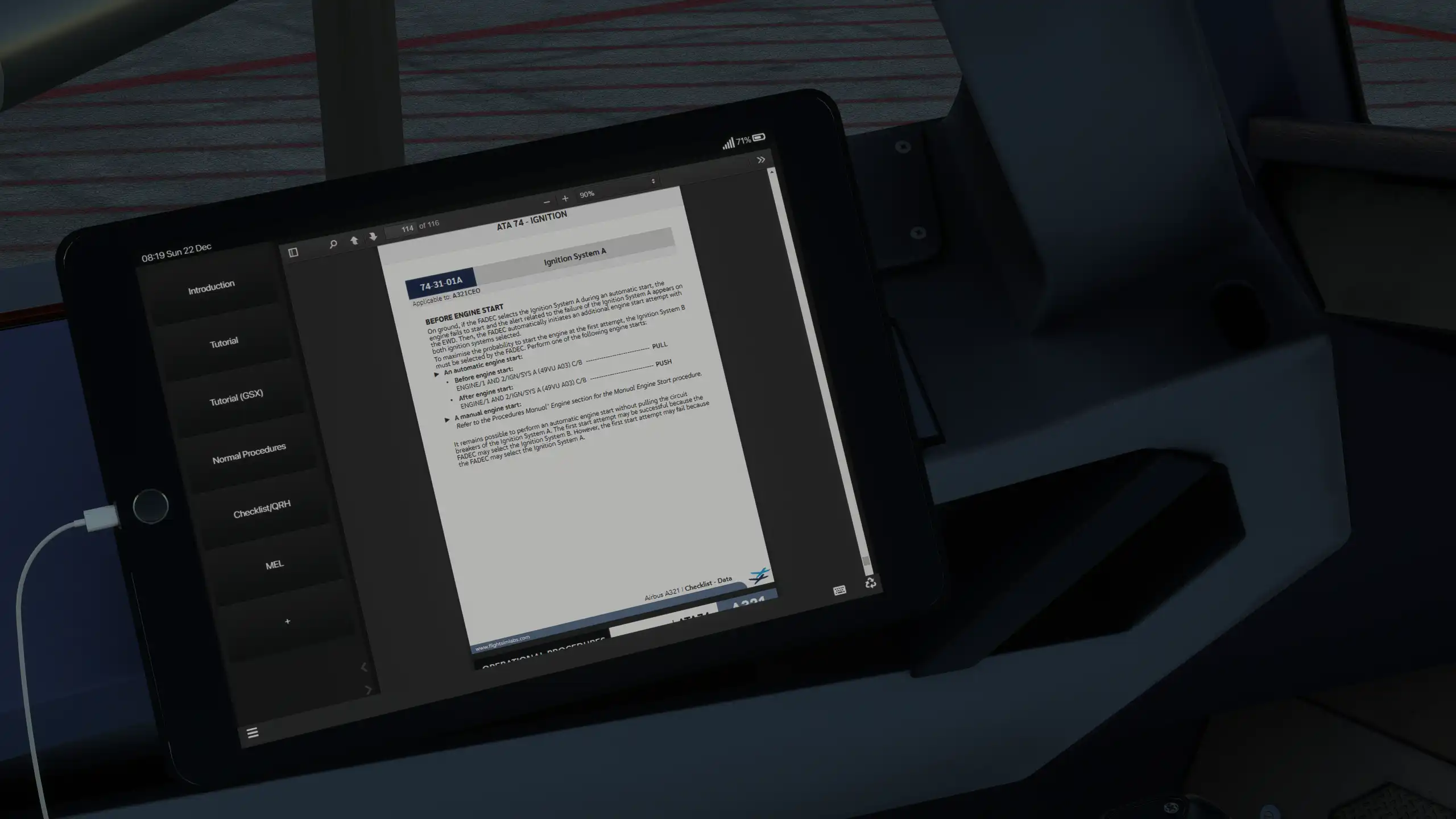

In a very clever fashion, FSLabs’ service based failure system uses an algorithm that takes airframe age into account to produce realistic failures, with their ratio, extent, and overall grounding possibilities increasing exponentially the older it is. Safe to say, my twenty five year old bird ought to bring a headache or two, and it sure did: my engine one starter was completely shot, forcing me to rummage through the MEL (Minimum Equipment List) document to find a workaround and get the old boy flying in time.

After a little bit of tinkering, the ancient machine was finally waddling to runway 26L for its take-off to Cologne-Bonn, one of my favorite airports to fly in and out of and one of my old “bases” during my Prepar3d days. Many CGN - PMIs were flown at the time with FSLabs aircraft nonetheless.

The first thing to become quite evident to me was how different it handled on the ground compared to every other add-on I have tried to date, feeling very similar to how their airplanes used to handle in P3D. You can really feel the weight of the aircraft as you slowly drive its nose wheel with the tiller, accompanied by a very subtle yet satisfying feedback from the terrain (I use my Xbox controller to control my tiller, therefore getting vibrations).

The sluggishness sure took a few minutes to acclimatize to after being so used to insanely responsive nose wheel inputs that could put any professional race car drifter to shame, but it wasn’t long until I was steering that airplane as smoothly as a forklift certified operator carrying a 450lb pallet of kitchen utensils.

The true moment of enlightenment happened as soon as I moved the throttle lever to FLX MCT and the old boy showed it still had a lot in it despite its advanced age, slowly yet steadily accelerating down the runway and non-reluctantly letting go of the asphalt to sail the not so blue skies in Munich towards Cologne. That was surely a “wow” moment as I felt the weight shift due to its pitch and the wings finally started doing their job and providing lift to 80 tonnes of steel, giving me a glimpse of what they had achieved with their external flight model.

The rest of the short flight went as uneventfully as one would imagine, with the occasional “Christ, this thing sure is a slow climber”, which is par for the course with the A321. All I could think of at the time was how excited I was to see how the flare behavior feels upon landing, something that many developers struggle to get right these days.

To make matters worse (for my anxiety), I had not touched an A321 in two years, with my muscle memory from yore being completely rewritten by the new planes I was flying in MSFS 2020. I had a vague remembrance of the theoretical part of landing it, which is slightly different to what you would use with an A320 due to its fuselage length and inherent tailstrike risk on both take-off roll and landing, requiring a very subtle and relatively flat flare to ensure not only a smooth and safe touchdown but also avoiding arresting too much energy and ending up with a whole lot of broken backs from pilots and passengers alike.

Figuring out the perfect landing technique for a new aircraft is oftentimes a harrowing moment, with a lot of trial and error before you acquire that ever-appreciated consistency that denotes our familiarity with the aircraft type. While I used to only fly Airbus in the Prepar3d days, things changed a bit since the advent of MSFS 2020, when I finally decided to give its biggest rival – the Boeing 738 – a fair go. To say I was rusty would be a bit of an understatement at that point.

Then again, the learning curve is part of the fun, bringing an extreme sense of accomplishment once you finally tame a new beast after many – or just a few, depending on the airplane and your skill set – legs.

My relationship with the WTF IAE in P3D was surrounded by love and hate, and I’d always slam it down every single time I took it for a spin after a long period of exclusively flying the smaller brothers (i was hugely into easyJet ops at the time, so the A321 was not really my most used variant). But I would always get the hang of it again after a flight or two and carry on as normal.

It didn’t take long until I was on short final for runway 32R in CGN, holding on for dear life on my faint memory of starting a subtle flare at 40 feet above ground level and then gradually reducing power whilst keeping a nose up attitude, initially around 2 to 3 degrees and then closer to 5 or 6 at the time of touchdown (to prevent arresting more energy than necessary at first). Whether that was it or not for the wingtip fence IAE, I did not remember for sure.

Sure enough, I stuck to my guns and initiated my flare at 40, gradually arresting the descent rate and things were looking rather positive until they were not (there’s a massive slope on the touchdown zone, and I don’t know if it’s a scenery issue or actually how it is in real life). For those unfamiliar to the dangers of sloped runways, they absolutely murder your landing rates, no matter how smoothly you land or whatever you do, it will always register as a rough touchdown. Unsurprisingly, it was in fact a rough reading at -253. Had the slope been a little less pronounced, maybe i’d have had a different result.

Evil slope aside, I felt in total control of the airplane from the moment i disengaged the autopilot at 1500 agl to the moment I initiated the flare and touched down rather violently, sending a gentle reminder to the distracted passengers that we had in fact arrived in Cologne. It felt alive, responsive, and connected, far from the usual feel I get with other Airbus add-ons in MSFS where it feels like the airplane is flying me rather than the other way around.

I could easily feel the weight shift as I initiated the flare, making it very easy to judge when to make the switch from the gentle initial nose up attitude to a more aggressive stance just before touchdown, where arresting more energy isn’t exactly a problem anymore as the ground is right there under you.

The return leg was definitely not one of my proudest moments, and it reminded me that strong headwinds and a heavy A321 will not go hand in hand if you are not careful enough: despite using the same technique, the airspeed was much lower than before due to the headwinds, which made it lose its lift as soon as I initiated the slight pre-flare, hitting the runway with a -370 fpm touchdown. An impactful arrival for sure.

The following legs (I tried to fly a couple of legs with all variants rather than a single flight to have a better idea of the handling characteristics and different behaviors) were all relatively tame after that. While not within butter territory, they were all safe and consistent landings.

On that note, I should add that I was very impressed by how incredibly consistent the results were if I followed the same landing technique: G forces, landing rate, pitch, all within the same ballpark, for many flights in a row (with similar-ish weather, of course). That’s exactly how one should expect an airplane to behave rather than being dynamically erratic on flare mode.

I went on to struggle for a bit with all the remaining variants (especially the CFM-powered ones), and one thing became very clear: they all fly and behave very differently, as you would expect. While it’s not night and day – for they are all A321s –, using the same landing technique for the A321SL on the A321WTF will absolutely bend the airframe, whereas the opposite will make you float to Narnia. Even the subtler differences (engine choice) will require slightly different input work and throttle retardation timing, albeit in a less significant manner compared to what is on the tip of the wings.

There is a baseline that applies to all of them, though, which is obviously very subjective and concocted from my empirical experience: initiating the flare at 40. As for when to idle the throttles, it will depend on the variant, as the wingtip fences will require you to keep the power on during the flare or else you will sink, and the sharklets would rather have you idle the thrust first before flaring, or else you will float like there is no tomorrow. Sticking to that baseline has allowed me to reach an acceptable consistency across all variants, without overpitching or floating excessively.

You can tell they really paid attention to these differences and how they impact the landing, forcing you to always be in high alert on final and very mindful of which variant you are flying, how heavy it is or isn’t, and that it isn’t an A320 or A319, thus also watching out for the flare input.

Modelling & Texturing - Flight Deck

The 3D work around the flight deck does not impress, but does not disappoint either. It’s well within the expected industry standard for Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 whilst striking a good balance between visuals and performance, which is really important when it comes down to running decently on a wide range of hardware out there (some developers seem to forget not everyone happens to own a RTX 4090 paired with an i9 14900K).

Knobs, switches, korry switches, levers, circuit breakers are all done very well and closely match real-life reference imagery, with perceivable depth and a satisfying feedback upon interacting with.

The texturing is extremely well detailed and the overall colour palette they went with closely matches cockpit pictures available online, reacting very decently to different lighting conditions without looking too cartoony or game-y. The wear and tear is very subtle yet decently done, managing to not look brand new but also not a century old, either.

Every single piece of text around the flight deck is fully readable, and there doesn’t seem to be any part of it where they cheaped out on the clarity. Regardless of how important or unimportant the label might be, it’s there in its fullest glory.

They have also carefully added smudges on the screens and dust specks, which is something that goes hand in hand with an airplane constantly flying passengers from A to B: there is no time to be wasted with wiping screens and stuff. The smudges on the windshield will dynamically increase as you fly the same airframe, with worse results during summer as that’s generally when the insect situation gets really bad.

Overall, the flight deck’s modelling is pleasing to the eye and the textures are sharp and clear while not asking much from your graphics card (other than the VRAM aspect, more on that later), allowing a lot of headroom for performance if you are not already limited by your processor.

Modelling & Texturing - Airframe

The same “does not impress, but does not disappoint” applies to the externals as well. It’s well within the industry standard but won’t drop any jaws so to speak. And very much like in the flight deck, every label is fully readable and given the same amount of attention, ensuring a consistent experience as you traverse through each nook and cranny of the airframe with the drone camera.

Combined with Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020’s powerful lighting engine, it’s a feast for the eyes of every Airbus enthusiast, evidencing how far we have come since the days of Microsoft Flight Simulator X and Prepar3d.

The model is light years better than their Prepar3d rendition, making it rather evident that it was in fact rebuilt from scratch to take advantage of the new – well, now quite old – platform’s capabilities.

Modelling & Texturing - Cabin

The cabin is a placeholder for now, as Flight Sim Labs have said they will eventually replace it with a brand new model and make it accessible from the flight deck, whereas the current one requires you to use the drone camera to go inside it.

With that in mind, it’s not too bad for a placeholder at all. While the modelling is a bit rough in certain areas and the texturing could have been a bit more high-resolution, we have to remember this is not a passenger simulator. A good cabin is a plus, sure enough, but it does not detract from a product whose main focus is simulating the intricacies of operating a complex airliner.

The fact it’s only accessible via drone camera also makes it so you cannot set wing views from inside the cabin, but that will eventually become a possibility once they release the new cabin.

Sounds - Internal

The internal sounds for both engine variants had a rocky start at first, with balancing issues that were quickly mitigated by updates. As of the latest version at the time of writing, it’s definitely much better than it ever was, not too loud and not too quiet either, with insane attention to detail on how much the aircraft and everything inside it (especially the trolleys) rattles during the take-off roll and during its initial climb.

They have also simulated how the sound changes based on altitude and barometric pressure, with different intensities and propagation as you climb to cruise level: as you get closer to your cruise altitude, the engine is barely audible in comparison to its intensity when taking-off, and then becoming gradually lower as you descend to your destination airport.

The sounds for everything clickable in the cockpit are solid and convincing enough, be it a knob, a switch, or a key on the MCDU. The startup orchestra is something I can never get enough of.

Sounds - External

The external sounds while on the ground are really good, with a convincing APU whine, solid hydraulic sounds when opening the cargo doors, and pleasant engine start concerts on both CFM and IAE. It sure does sound like a living machine.

The soundscape during cruise is a bit underwhelming, though, but still within acceptability.

Systems - Fly-By-Wire

The fly-by-wire implementation is one of the best I have ever seen in a home simulator, effortlessly handling maneuvers and approaches no matter how complex they may be, just like the real airplane. You can really trust the autopilot will get you to your destination, requiring next to no babysitting other than watching out for failures given it also features a service based failure system, meaning anything could go wrong at any given time and being near the controls would be very optimal in that case.

Regardless of whether it is an RNAV, ILS, VOR or Visual approach, the airplane will handle it like a champ and the end result will only depend on your capabilities as a pilot (or just let it do everything for you if it’s a CAT3b approach. It autolands by the book!).

The code was built to handle the “realistic” turbulence settings in MSFS, which many developers recommend turning off as it generally upsets their autoflight systems. The Labs, on the other hand, plows through it like it’s nothing.

Systems - VNAV & LNAV

The vertical navigation has been absolutely spot on in all the flights done so far, respecting speed and altitude restrictions, and always arriving at the penultimate fix for glideslope and localizer capture at the expected speed and altitude. There was not a single time where I was too high on the 10 nautical mile final.

The lateral navigation, as briefly touched in the fly-by-wire section, has also been immaculate as far as my experience went (quite a substantial amount of flights at this point). It handles all the turns very gently and smoothly, without overbanking or anything. Definitely within the best implementations in the simulator.

Handling

As previously mentioned, the handling is really solid, with a good sense of weight and responsiveness, with no input lag oddities or anything of the sort, making it very intuitive and welcoming for new pilots, and bringing the sort of precision and behavior that Airbus veterans have come to expect.

The landing behavior is unlike anything else in the simulator, making you feel in total control of the aircraft and behaving closer to the real thing, to the point you can follow the techniques in the FCOM down to the line with similar outcomes. Sticking to a specific technique will always produce the same results as long as the weather and weights are somewhat similar (I have tested that myself with all variants).

With that being said, the airplane will absolutely punish you if you are not stable on short final, with an above standard descent rate, far below or far above the reference speed for landing, etc. A stable approach is key to producing consistent results.

The variant at hand will dictate the specific technique needed, as every one of the four variants has their own behavior on flare, with more or less floating tendencies, requiring the pilot to be always aware of what they are flying and demanding a certain level of familiarity before you can start consistently buttering the bread. Mastering the four of them is quite rewarding, I must say.

While the differences between variants are said to be subtle, they are not all that subtle, not even in real-life. If memory serves me, one of the North American carriers with both wingtip fences and sharklets had a sticker on the flight deck to remind the pilots they were flying a sharklet equipped variant. If the difference was in fact so subtle, why would that be important to reinforce? Just to remind the pilots they will be saving around 3% more fuel?

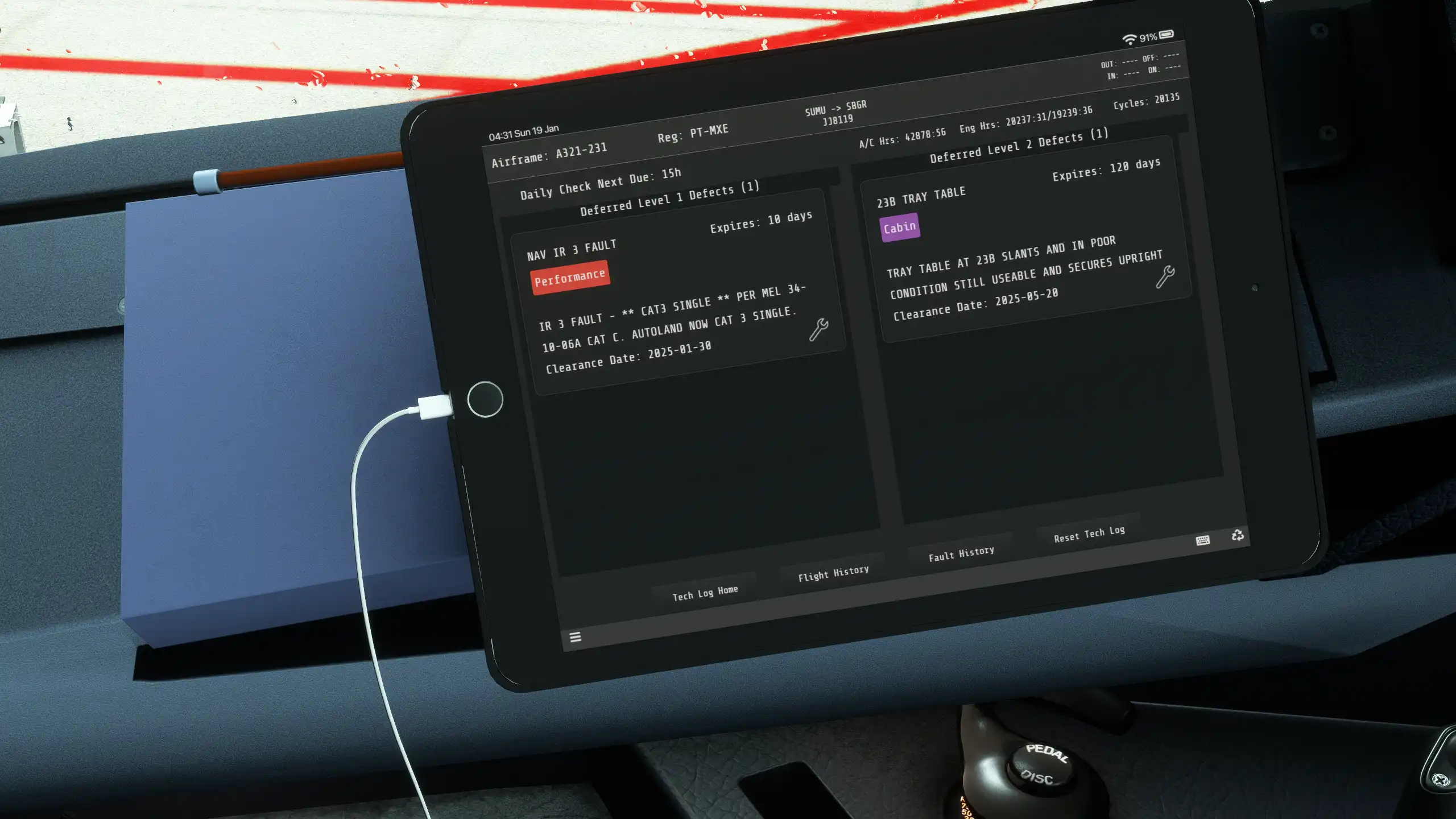

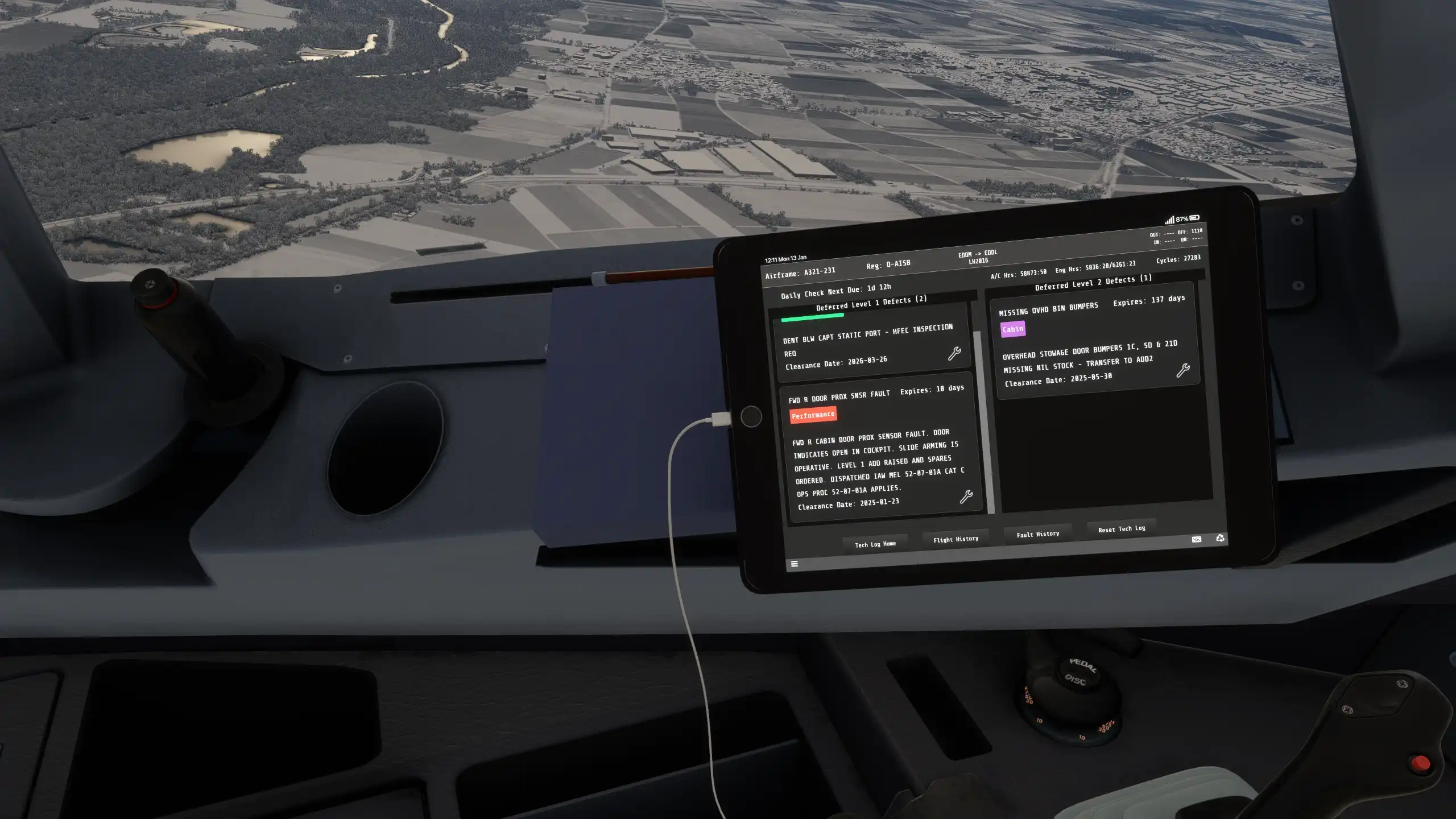

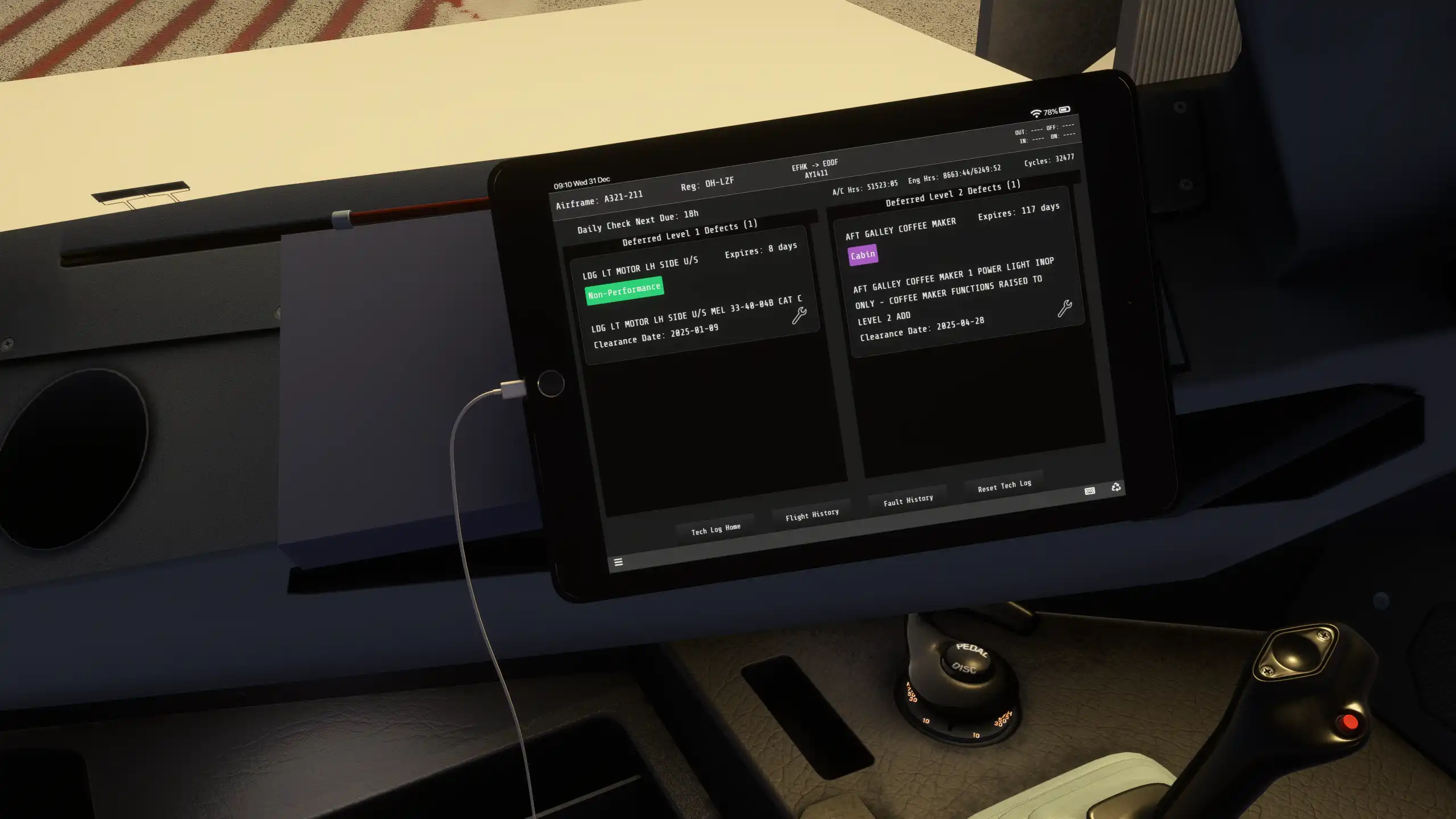

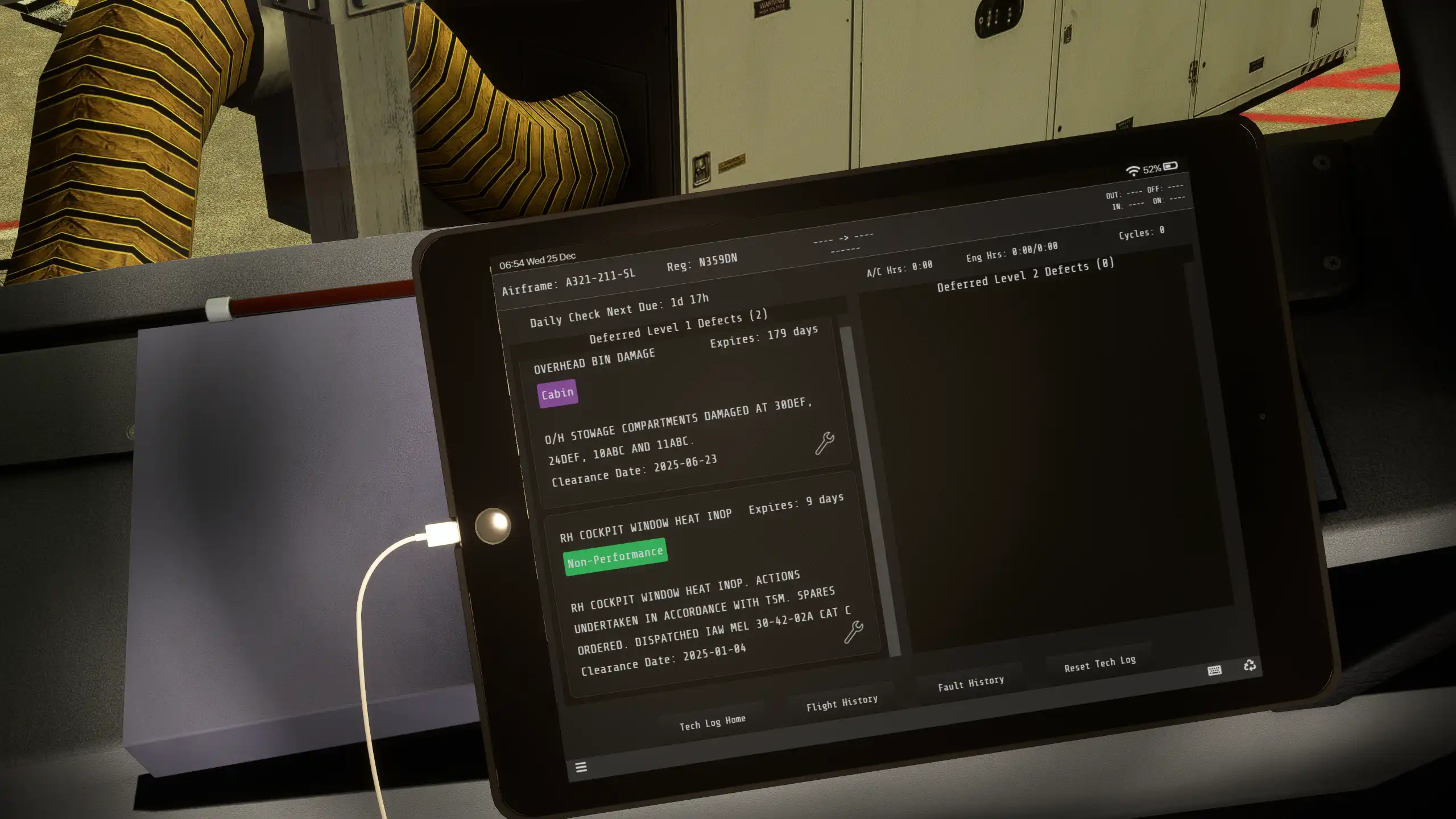

Tech Log and Service Based Failures

As briefly mentioned during the “First Impressions” section, the FSLabs A321 features service based failures, with varying ratios and probabilities based on how old the airframe is (by MSN) and airframe/engine hours, meaning an older plane will be more likely to fail at any given time during the flight.

Whenever you load into a new airframe, there is a high chance there will be something wrong with it, although generally of minor extent, like a broken overhead bin, missing magazine pockets, etc., which does not mean you can’t stumble upon a broken APU, a dead engine starter, an inoperative reverser, which will then lead to the decision of whether to straight up fix it or carry on with the issue depending on whether the destination airport(s) will accommodate the failure(s) at hand.

I had a windshield heater problem during one of my Delta flights with the A321SL, and had to make the choice on whether to fly to Boston from Minneapolis anyway or stay grounded, as the Minimum Equipment List said it was not to be flown under icing conditions (and it sure was cold in MSP!). I decided to be stubborn and fly anyway as the left windshield heater was still intact and get it fixed in Boston.

It’s a really fun dynamic that is rarely seen in add-ons. Many do offer failures, which you have to either trigger yourself or have them happen randomly based on real-life probabilities, but never to this extent which is pretty close to what real life pilots have to experience on a day to day basis whenever they hop into an airplane. Their tech logs will always have something in there to be taken care of. At the end of the day, commercial airplanes operate everyday, and intensive use will eventually lead to failures, be it because of wear or just randomly bricking to make your mondays even better.

I always look forward to peeking at the TechLog whenever I log in for my daily adventure and referencing the Minimum Equipment List to troubleshoot – or ignore – it depending on the severity. It sure makes it feel more like a living machine, giving it all the reason to stick to one specific airframe and seeing just how bad things can possibly get.

In a sense, it makes it so every flight is unique and makes it all the more important to closely monitor the aircraft during cruise rather than just tabbing out and doing something else (I might be guilty of that sometimes).

A few days ago, I was watching a friend stream the A321SL on Discord from Denver to Detroit, and it was raining during the descent, which prompted him to activate the windshield wipers. It turns out he was a bit too fast still for wiper usage, making the right side wiper break and get stuck. We first thought it was a bug, but surely enough it showed up on the Tech Log afterwards, pointing to overspeed being the root cause. There are not many add-ons out there where that can happen and it makes it so you really have to stay on top of everything. I assume the same happens if you deploy the flaps above their predetermined deployment speed, for example.

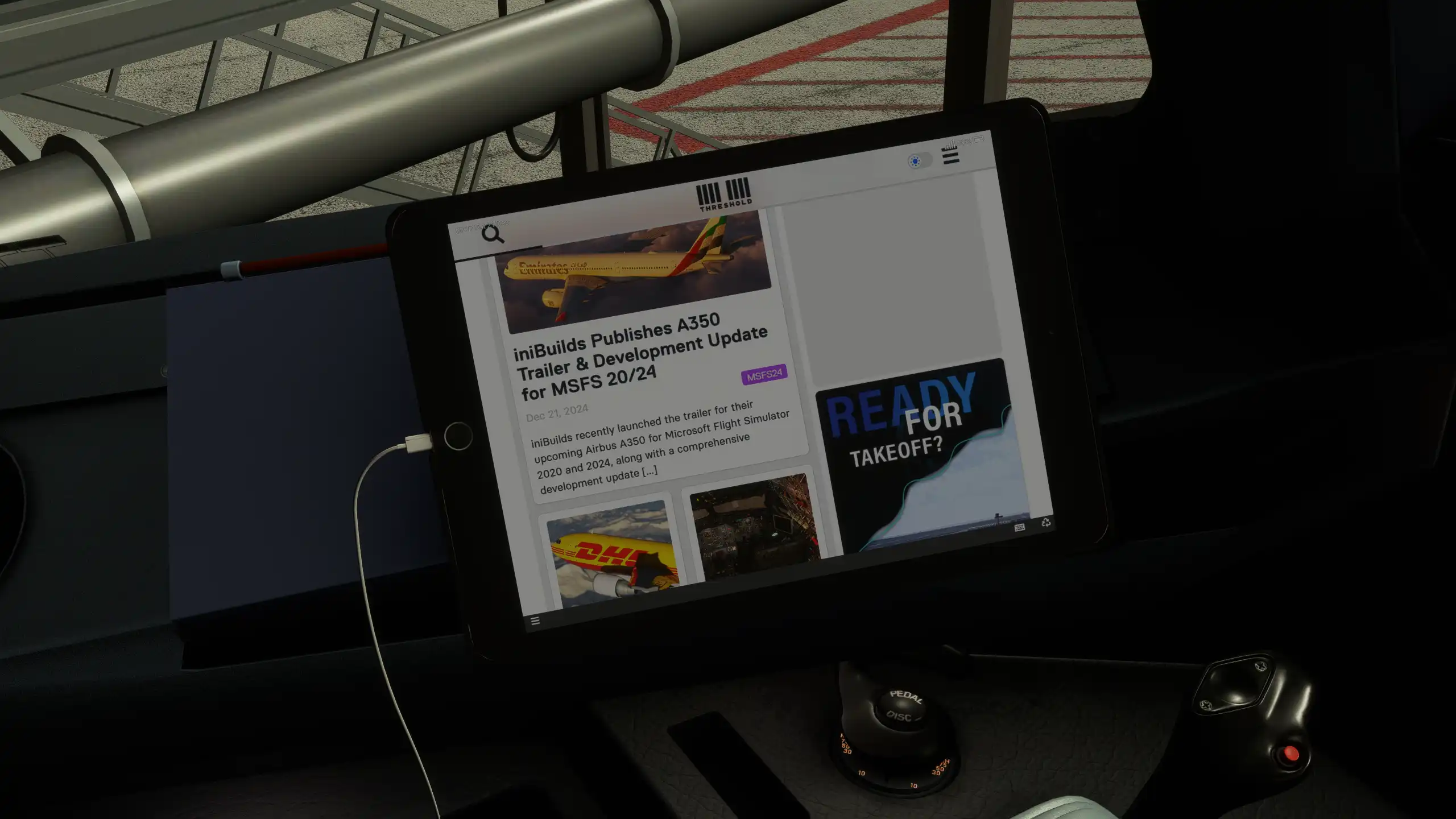

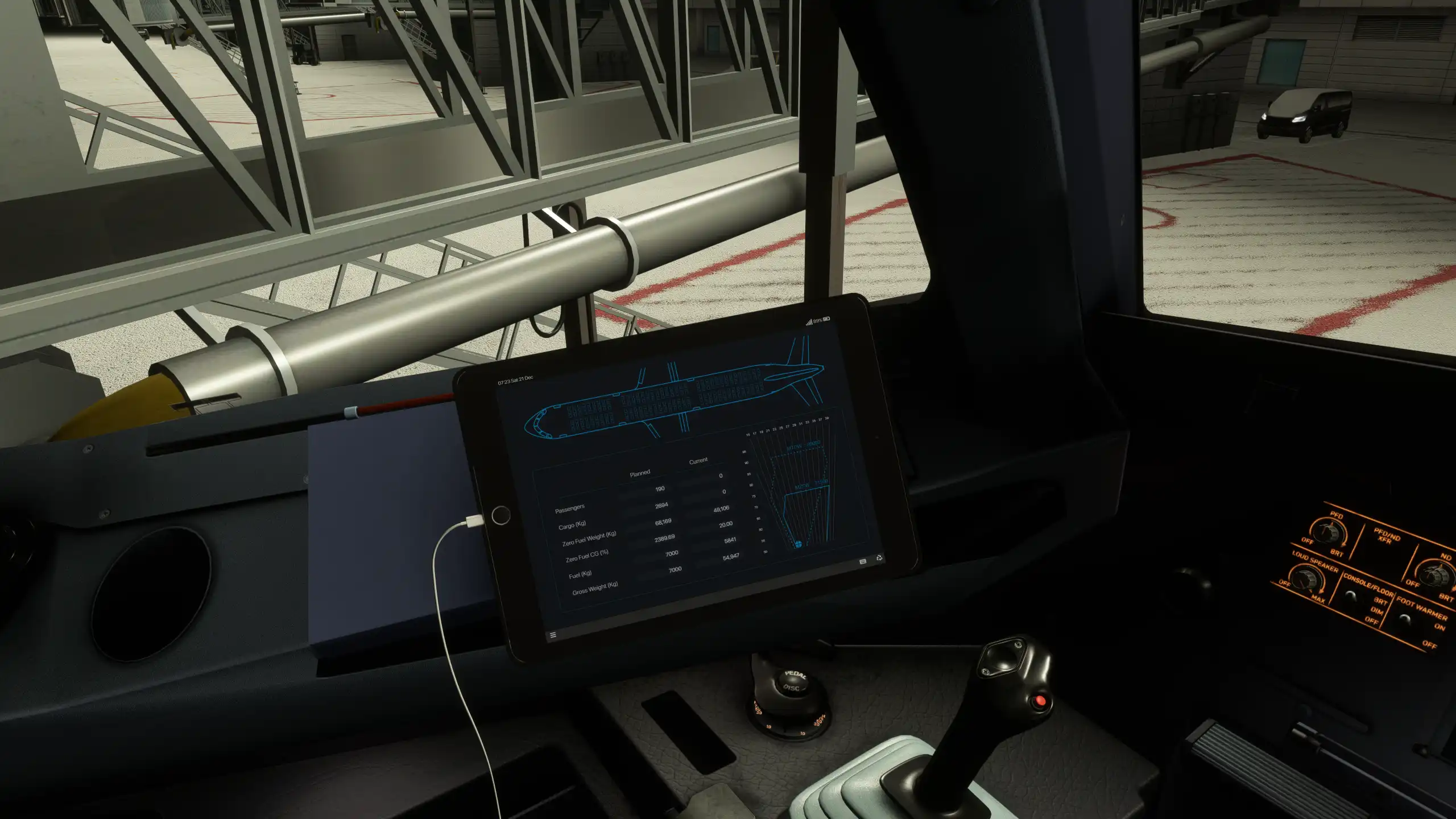

Electronic Flight Bag

The EFB, like in most add-ons these days, is the “heart” of the aircraft, where you interact with the ground crew, handle weight and balance, performance calculations, charts, and all the bells and whistles we have grown accustomed to.

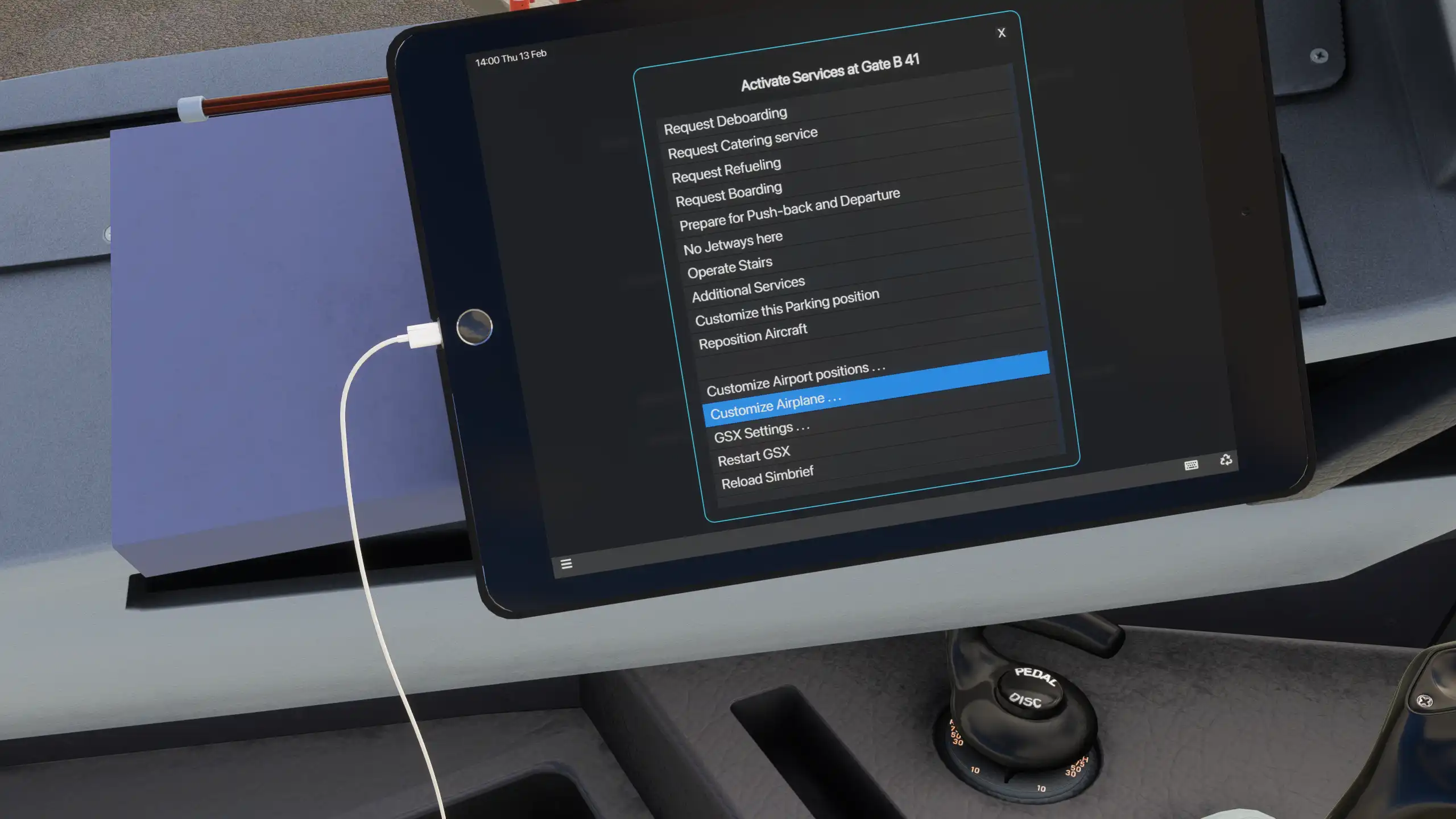

Flight Sim Labs takes the EFB experience to the next level by letting it automatically control Ground Services X (by FSDT), wholly eliminating the need to ever bring the GSX menu up. It seamlessly handles every step of the way and synchronizes with the ATSU for boarding, fueling, loadsheets, etc.

This degree of automation essentially means you don’t really have to tab out of the simulator or use its menus for anything, as the ATSU will also provide you with weather requests, the EFB will display your operational flight plan, handle all calculations, and even browse the internet if need be (yes, it can do that!).

The only point of criticism would be its sluggishness at times when navigating through the “apps”, but everything else is pretty solid and intuitive.

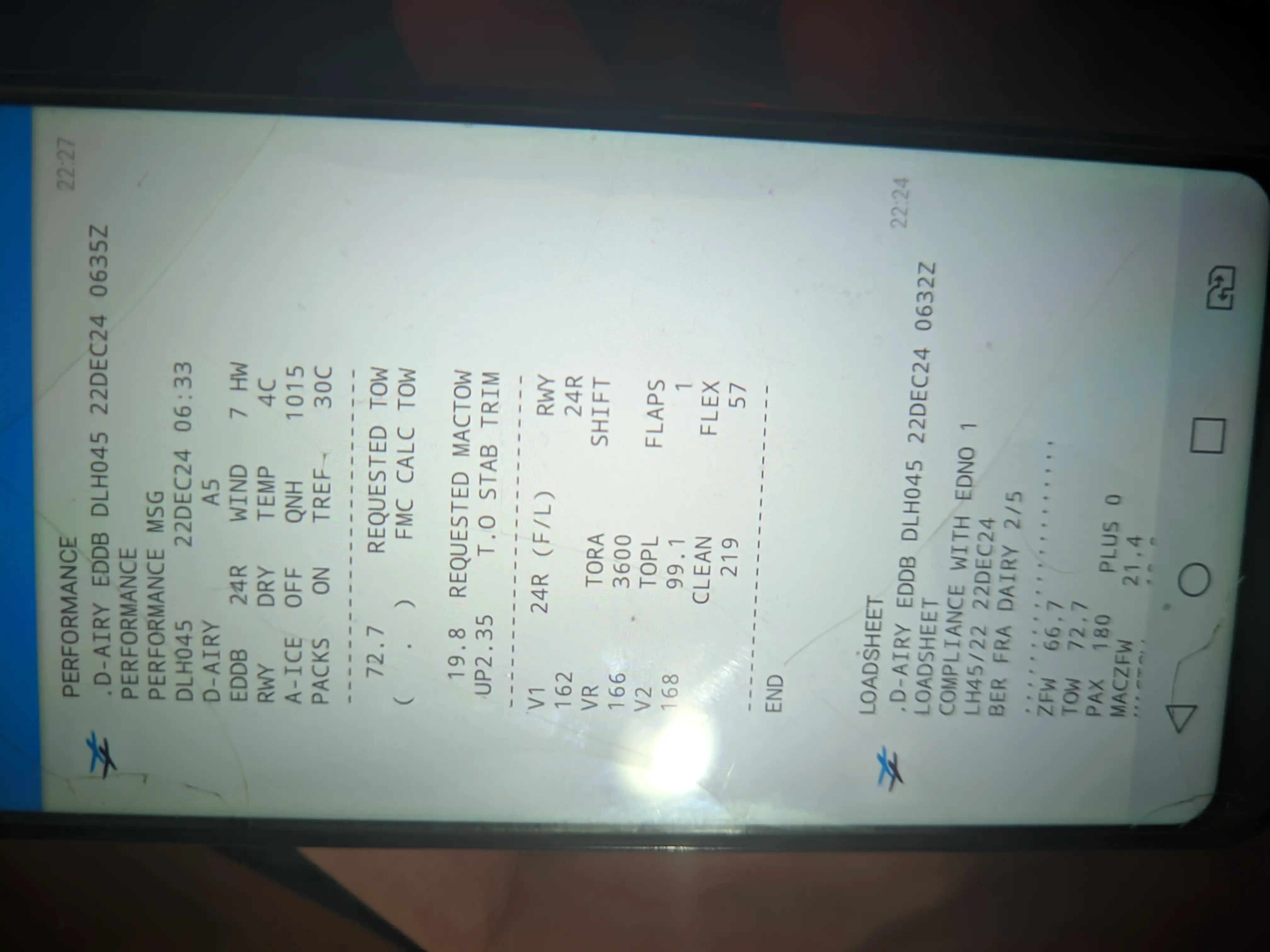

The take-off performance calculator data allows you to calculate your speeds from basically any intersection, whilst displaying all the information in a very intuitive and easy to understand manner. It contained intersection data for all the airports I have been to so far.

The EFB also contains all the documentation accompanying the aircraft, including a quick start guide, a tutorial flight, a GSX tutorial, the Minimum Equipment List, and the checklist. Users can also freely add any other PDF files by clicking on the “plus” symbol.

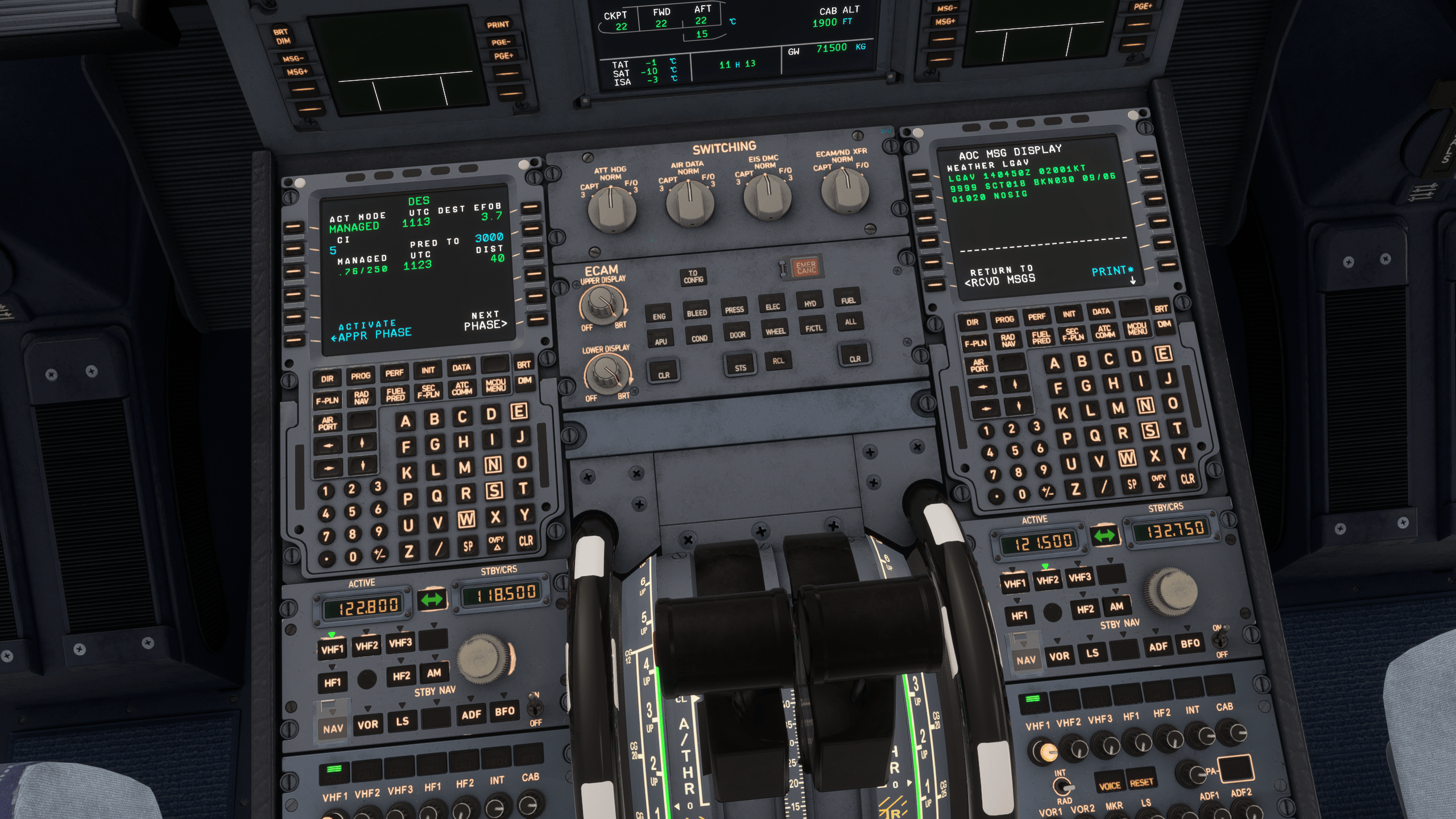

ATSU

The Air Traffic System Unit (ATSU) – successor to the ACARS Management Unit - is deeply simulated in the FSLabs A321, allowing users to request pre-departure clearances, weather data, SIGMETs, communicate with other aircraft in the network via Hoppie ACARS, get gate and slot information, and much more, mirroring the experience and overall functionality of a real unit.

It’s possible, for example, to pre-select a parking stand from within the ACARS and have GSX automatically assign that spot to your aircraft once you land, removing the need to directly interact with the add-on.

Just like the real world counterpart, it’s possible to report aircraft and operational data to the “airline”, and have that information printed either physically with a thermal printer, or via software to a file or sent through Pushover, a handy app that integrates with the FSLabs bus.

Weather Radar

As of mid-January, the add-on now features a realistic simulation of the Rockwell Collins weather radar, which allegedly interacts with Microsoft Flight Simulator’s default weather engine to provide accurate radar returns without the usual limitation of being rather dull as is generally the case with any other implementation of Asobo’s weather radar API: instead of being overly sensitive and showing detail that a real weather radar would not pick up under any circumstances, FSLabs found a way around it only to display what the actual unit would be able to detect.

I have extensively tested the weather radar implementation in a nearly month-long period since the update rolled out to ensure its behavior would be adequate regardless of weather conditions. From what I have seen so far, there was not a single moment where I thought the depiction was slightly off or more exaggerated than it should have been, the latter being generally how it goes with the default API without tweaking. Whatever FSLabs did with their custom implementation worked wonders, with only precipitation spots being shown, creating a much more convincing overall output.

Then again, take my five cents on the matter with a grain of salt, as I am not a weather radar specialist (or a real-life pilot, for that matter), but it does seem to provide subjectively better —and probably objectively also—outputs.

Some of the inherent limitations that go hand in hand with the way Asobo made their radar system work persist, though: it’s currently not possible to use manual tilt, with auto-tilt being the only working mode and being slightly odd at times, which is just how the API works at the end of the day, unfortunately. With that in mind, though, it’s safe to say they managed to juice a rock, all things considered, delivering a weather radar that is far superior to any other implementation in Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 as of today’s date.

Performance

My System: 32 GB RAM DDR4, Ryzen 7 3700X, Nvidia RTX 3080 10 GB, 3 TB SSD (non-NVMe).

As far as graphical processing demands go, the FSLabs A321 isn’t exactly very demanding, being actually even less intense on that aspect than PMDG, for example. But things change a little when CPU load and IPC requirements are taken into account: with a fast CPU, it performs better than most airliners, but not so much if the CPU is a bit old like mine. Held back by my limited IPC, I average less than 30 fps during cruise, and 30 on the ground with the engines off (my frames are actually locked to 30).

When a faster CPU is taken into account, though, the figures are completely different. A mate of mine has a 7800X3D and he manages to average well over 60 fps consistently, better than what he yields with PMDG aircraft according to his comparison.

That’s easily explainable by the airplane’s sheer complexity, deeply simulating all of its systems and also doing external flight model calculations, all at the same time. A fast CPU will absolutely thrive and plow through all that workload with ease, whereas something like what I have will just barely allow it to sit within playability levels.

But not all hope is lost for those like me with a five year old CPU barely hanging on by a thread: Lossless Scaling! For the unaware, Lossless Scaling captures the game window, overlays another window on top of it with interpolation, generating frames and warranting additional smoothness during all phases of flight (or just for landings in my case). While some add-ons glitch out with LS, getting slight – or substantial – input lag, the FSL seems to have no issues with it whatsoever, allowing me to fly into virtually any payware scenery, no matter how complex it is.

LS is especially handy for those owning a GPU with limited VRAM, as DirectX 12 (required for standard frame generation) is rather unkind with maxed out video memory, leading to stutters when panning and overall bad performance, and Lossless Scaling does not really need DX12 to work, allowing you to run MSFS 2020 in DirectX 11 and therefore avoid all of the downsides of having your video memory maxed out in the simulator.

On that video memory aspect, I have noticed the FSLabs A321 is a bit too heavy on VRAM sometimes, leading to some brief freezes while switching cameras. Then again, I’m running the sim in 1440p and ultra settings (including textures), which might just be a bit too much for my 10 GB of VRAM. It’s just something to keep in mind, I guess.

Conclusion

For $69.95, you get what is arguably the best Airbus A321 simulation in the market as of February 2025, with one of the most impressive flight models I have ever experienced in a simulator. Each and every variant behaves in their own specific way, requiring a steep – yet rewarding – learning curve before you can master the art of flying them properly.

While it does not have the prettiest 3D model, it more than makes up for it in overall system depth, flight dynamics, and immersion. There is absolutely nothing in the simulator at the moment that could top what it offers in terms of overall immersion. The experience is unparalleled, from the moment you enter the flight deck and turn the batteries on to the moment you call it a day after a full day of flying back and forth or just a single leg, there is nothing but absolute joy.

The service based failures make it so you have to always be mindful of what is going on with your airplane and plan accordingly, paying close attention to the minimum equipment list PDF and making important decisions as to continue with the flight (when possible with workarounds), ground the airplane, or risk it all just for the what-if (something you can’t really do in real life if you are sane enough, but well within the possibilities of a simulator).

All in all, Flight Sim Labs has managed to do the impossible and offer a product that is a notch above the competition (which is also pretty damn good), thus making it a justifiable purchase for those wishing to really get as close as possible to the real thing in both immersion and realism.

A huge thank you to FSL for providing us with a review copy!

Share this page

COMMENT ADVISORY:

Threshold encourages informed discussion and debate - though this can only happen if all commenters remain civil when voicing their opinions.